Never Turn Your Back on the Ocean

NEVER TURN YOUR BACK ON THE OCEAN 1

Architecture loves the sea. Sparked by Jesse Reiser’s marine flirtations in New Fineness2, this metaphoric romance is manipulated by Patrik Schumacher who claims today’s digital-communicative network as architecture's new fluid surface. Reiser’s notion of poise is surpassed by Autopoiesis’ scintillating clarity. Deep within this liquid body lurks something more menacing: the black hole. A startling evolution of Deleuze and Guattari’s Faciality, Zaha Hadid Architects’ Galaxy Soho Beijing exemplifies the role assumed by this monster of the deep. The building and its authors exhibit an architecture of introversion. Only by actively challenging this dubious act, a mission demonstrated by the art of Carey Young, may architecture liberate itself from black hole’s g!ravitational lure.

In Beijing, Schumacher propagates his brand of architectural Newspeak3. This reformed architectural dialect4 eugenically transcends Post-Modernism’s urban cacophony to “coordinate pragmatic concerns” while articulating them “with all of their rich differences and relevant associations”5. However, it is unclear remains to assess this relevancy6. The human, now described as a “psychic and organic system”7, leaves streamlined instruments of autopoietic expression to become guiding lights within an architectural expanse that no longer allows “every individual architect to do as he or she pleases”8. With blinding, plasticine glory, Galaxy Soho performs its luminary task. A lacunary moment within an increasingly discontinuous urban fabric, the term ‘galaxy’ is no misnomer. A nebulous and rotational milieu interested in little more than “synthetic effects”9, Soho creates organizations rooted primarily in “internal and iconographic needs”10. Galaxy Soho’s success is dependent upon repetitions’s reign over substance11. Favoring deep internal instinct rather than intellect, Soho recoils and wraps around itself. Visceral volumes exist at the core of this a!rchitectural black hole. Its repetitive rail-like facade becomes the path along which gravitational pulls refresh their charge.

A fully formed black hole, Galaxy Soho becomes a veritable fortress. Soho exemplifies the Faciality machine; a despotic assemblage that achieves its power through redundancy, its concentric circling of black holes intensifies their agonizing pulls12. Entering the chasms of Galaxy Soho, one is “pinned to the white wall and stuffed in the black hole”13. It is a hole so powerful, within a world so involuted, that no escape seems to be offered. Amidst Galaxy Soho’s gyrating sinew, the individual is sent into a hopeless tumble. The profiles of its balconies become confused for lines of flight, appearing as opportunities for circumvention but instead providing endless circuits. Soho’s concavity is matched only by the sea’s foreboding turbulence. The black hole has become a liquefied continuum. The white wall which once provided vertical orientation has unraveled, now impossibly interwoven with this newly distributed and encompassing gravitational void. Composed of numerous black holes cresting at different moments, the maritime landscape14 assumes an unceasing rearrangement of force. The white wall, reduced to a thin demarcation, is at the whim o!f these fluxing powers, its relationship with the black hole becoming evermore tenuous and its existence threadbare.

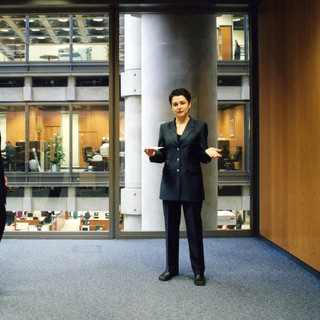

Diving into the black hole’s inky waters, artist Carey Young navigates their Sargasso depths with deft agility. Resurfacing, she confronts the suspect economic and political associations architecture has developed, responding to the merging lexicons of business and creative spheres15. Young’s I am a Revolutionary (2001) reveals the relationship between linguistic manipulation and Deleuzian introversion, divulging both the absolution of the artist’s creative autonomy and its subsequent possession by corporate entities. Illuminating the now one dimensional nature of the term ‘revolutionary’ Young exposes the ease with which, through repetition, language is strengthened to serve specific agendas, be they financial or architectural. Young’s quest to convince her audience that she is, in fact, a revolutionary indicates the often self-proclaimed nature of this title. Drained of its significance, Young’s repetitive rehearsal points to the sinister face of corporate servility. ‘Revolution’ has now become ubiquitous as Young’s line ‘I am a revolutionary’ may be “rehearsed by anyone until they sound convincing”16. Are corporations now militarized training arenas, existing to create anonymous revolutionaries? Have they become the new avant-garde? Young confronts these issues. Political and economic activity are now inseparable from her work’s identity. They are tropes present at the conception of her art and their a!voidance is impossible.

Soho is symptomatic an architecture which falsely maintains its status as post-political. Carey Young swiftly and expertly exposes the forces active behind Soho’s scrim. Its theoretical justifications and aesthetic promises are revealed to be as calculated as her entrepreneurial alter-ego. Where the forms of ZHA are implicit in their politicalization, Young’s work remains explicitly17 political. Ultimately, countering Autopoiesis, Young assembles a framework which encourages radicality18. In doing so, she constructs subjects who, in contrast to her neo-liberal performance, are empowered to act polemically. Young revives her viewers. S!he awakens them from their slumber. They again exist to challenge the relevancy and validity of suspicious architectural forces.

NOTES

1Noble, R. (2009). Utopias. London: Whitechapel Gallery. pg. 219.

“It is clear how the ocean, a threatening remnant of the flood, came to inspire horror...no matter how zealously they worked, men would never be able to recreate the antediluvian earth, on whose surface the traces of earthly paradise could still be seen” — Alain Corbin, The Lure of The Sea

2 Reiser, J. (2001). ‘The New Fineness’, ASSEMBLAGE, VOL. 41: MIT Press. pg. 65.

3 Noble, R. (2009). Utopias. London: Whitechapel Gallery. pg. 36.

Gazing into a future that is now nothing but a distant past, George Orwell outlines his principles of Newspeak. Serving as a total reconstruction of existing language, Newspeak is a syntactical upset. The babble of its refigured jargon aims to solidify the meaning of its new terminology so rigidly that old meanings are forgotten, unable to exist within this new “streamlined instrument of expression”. Simultaneously advancing its own agenda while smoothing any verbal dissonance, it is a language whose goals are calmly calculated and eerily eugenic.

4 Schumacher, P. (2012). The Autopoiesis of Architecture, Volume II. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. pg. 680.

This linguistic reformation is accompanied by a dazzling array of heuristics, taboos, and analogies promising endless degrees of variegation and adaptability (two general terms that act as Parametricism’s fail-safe).

5 Ibid..

6 Perhaps no one will assume this task.

7 Ibid. pg. 715.

8 Ibid. pg. 710.

9 Petit, E. (2013). ‘Involution, Ambiance, and Architecture’. Log, (29): Anyone Corporation. pg. 27.

10 Ibid. pg. 29.

11 Ibid. pg. 28.

In fact, it is best not to question the meaning behind this object’s generation because, as Petit notes, “cerebral analysis of the [source] code yields nothing”.

12 Deleuze, G. and Guattari, F. (1987). A Thousand Plateaus. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. pg. 214.

13 Ibid. pg. 212.

14 Ibid. pg. 214.

15 Noble, R. (2009). Utopias. London: Whitechapel Gallery. pg. 194.

16 Ibid. pg. 198.

17 Ibid. pg. 199.

18 Ibid..

Young states that her work “is not a question of...offering some kind of solution, but of creating pieces which immerse the audience in the problem...for the sake of engendering a discussion”.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Deleuze, G. and Guattari, F. (1987). A Thousand Plateaus. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. Noble, R. (2009). Utopias. London: Whitechapel Gallery.

Petit, E. (2013). ‘Involution, Ambiance, and Architecture’. Log, (29): Anyone Corporation. pp.25-32. Reiser, J. (2001). ‘The New Fineness’, ASSEMBLAGE, (41): MIT Press. pg. 65

Schumacher, P. (2012). The Autopoiesis of Architecture, Volume II. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons.